Explore the fascinating interplay between social structure and the way people share money, as revealed by a groundbreaking study co-authored by an MIT economist. Discover how age-based and kin-based societies exhibit strikingly different patterns of informal finance, with far-reaching implications for local economies and poverty alleviation.

The Power of Social Ties

Worldwide, people often fall back onto informal financial systems, borrowing and lending money along their social networks. Getting to grips with this dynamic is vital, because this can throw light on how local economies work and assist in the fight against poverty.

A new study, co-written by an MIT economist, describes a quirky case in East Africa: whether money tends to move more efficiently when it flows through family groups or age-based associations. The finding highlights the strong influence of social structure on financial linkages and behavior.

In the age-graded societies, individuals are inducted into adulthood with one another and retain support networks based on their year group rather than extended family. These patterns were similarly reflected in their financial relationships. In a society organized by age, when someone get a cash transfer, he spends most of that money on other people of his own age– not on younger son or old moms.

The Structure of Society: Kin-Based vs. Age-Based

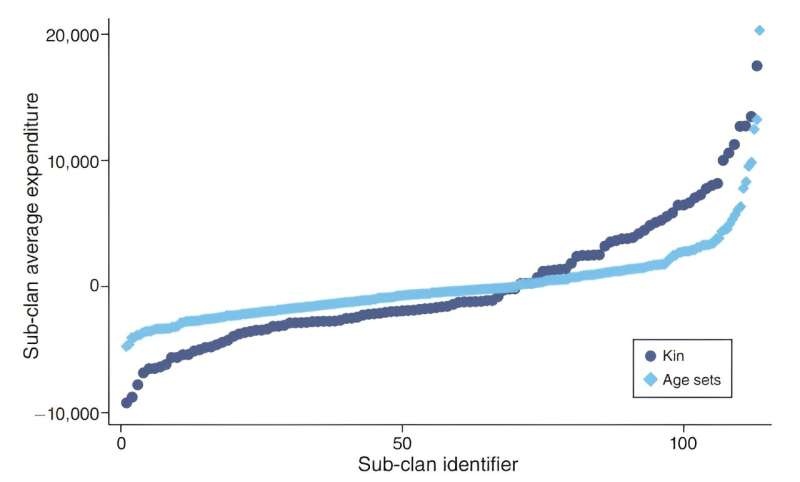

The study offered a revealing contrast between kin-based and age-based societies. In family-based social structures where the extended household is the building block of society, money is likely to be shared or sheltered within the family, not between age groups.

This divergence of financial trajectories has clear health consequences. Grandparents in kin-based societies frequently redistribute their pensions to ensure greater than half of orphans getting treatment for malnutrition-live with carers, so many children return home. That is… young and old are now most exposed to two basic life risks but in age based societies these sorts of inter-generational financial flows work much less well.

On the other hand, in age-based societies the age sets generally cross cut lineages or extended families making them more equal within the group. Meanwhile, relative poverty could be far higher in kin-based groups where some entire families are much more hard up than others.

The policy and research implications of these findings are significant, underscoring the importance of taking account of social structure in the design and evaluation of social programs and financial policies.

Conclusion

Not only is this first-of-its-kind study illuminating, it shows the concerning extent to which social structure plays a pivotal role in how money is circulated amongst people at all levels within an economyophile system — and what can happen as a result when that fails. Policymakers, who appreciate the distinctions kin based and age-based societies have so that they can come up with interventions that certainly speak a little bit more directly to what people in these communities need as well as where are front is vulnerabilities lie. High on the list of considerations for public policies designed to reduce inequality and ensure financial inclusion are, just as the researchers note, social structure.