Discover the astonishing story of how leafcutter ants became fungus farmers 60 million years ago, long before humans ever began cultivating crops. These remarkable insects have developed a sophisticated farming system that has stood the test of time, even as the climate has changed dramatically over the millennia. Explore the cutting-edge research that has uncovered the genetic secrets behind the ants’ successful fungus domestication, and learn how these findings could inspire new approaches to sustainable agriculture.

Leafcutter Ants / The Original Fungus Growers

Hundreds of millions of years before human civilizations sprouted up, a lineage of ants known as the attines established their competitive edge by becoming masterful fungus farmers. These impressive insects have been farming their fungal crop for more than 60 million years and so predates human agriculture by some 10,000 years.

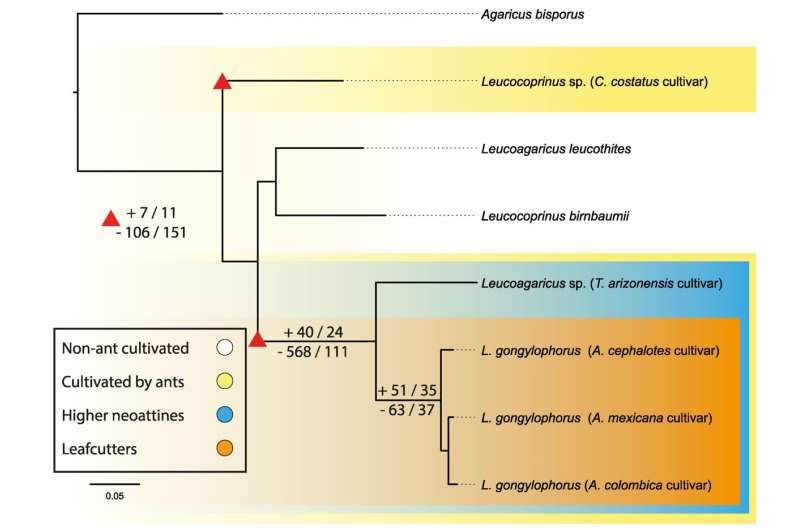

Among the attine farmers, leafcutter ants are the most advanced at producing food and have developed a co-evolutionary relationship with their fungal crop, Leucoagaricus gongylophorus. Ants plant, protect, and lovingly tend their fungus -feeding colonies through constant care and cultivation of a specialized fungal crop that the ants grow in gardens maintained within high-energy compost-colonies. The result is a cohabitation that has enabled the leafcutter ants to spread across several types of ecosystems: from the wet rainforests in South America to the arid shrublands of north Texas.

Unraveling the Mysteries of Ant Farming Biology Grayson Articles

Leafcutter ants are social insects with a Pheidole cultivar and ataulfo (Journal of Molecular Evolution)Researchers have made an unexpected find in a… However, by sequencing the genome of this fungal crop grown by these industrious insects, scientists have determined the essential adaptations that have enabled it to prosper in captivity under their ant custodians.

University of Copenhagen and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute New groups of genes have enabled a parasitic fungus to ascend the tree-tops;) © Jakob Kostelecki; Caio Leal-Dutra A new study led by Assistant Professor Caio Leal-Dutra at the University of Copenhagen’s Department of Plant and Environmental Sciences is ‘one into the weeds’;) with probably singlebes out among adopting ants in rainforests finding) new ones;) Other findings show that two groups-if-you-would-just=me six varieties* +3 where=the fairest and which has–viruses may be discovered ldc). The genetic changes in this fungus allows it to degrade plant material and accumulate nutrients for the benefit of the leafcutter ants, which makes the fungus an ideal crop.

The researchers found that the fungus also harbors a great number of mobile genetic elements — so-called “jumping genes” — in its DNA. All of these factors can change the fungus genotype so rapidly it can adapt to any challenge and evolve according to environment changes. It turns out that this kind of flexibility has been very important for the continued success of ants as farmers.

Agriculture Sustainability — What Humans Can Learn from Ant Farmers

Given the challenges that humanity faces in agriculture, agro-ecological methods of pest and disease suppression appear increasingly attractive particularly in a future influenced by climate change, so the evolutionary solutions exposed by the study of leafcutter ant farming represent an area ripe for further research and potential innovation.

“Seeing how these ant-farming systems persist over the long term may idea-spark new approaches to imagining sustainable agriculture,” says senior author Jonathan Shik from University of Copenhagen. According to Gaggio, “While we are not at the point where we can label ant-farming as a model system for human agriculture, this work shows us how genetic changes may help farmers ultimately achieve both yield and environmental stability.”

Studying the genomic adaptations of the leafcutter ants’ fungal crop offers important lessons about how farming can arise de novo as a complex variant on an ecological interaction (rather than be innovated by humans entirely outside nature). The hope is that this knowledge could be used to create more resilient and sustainable agricultural practices, so that we are better able to feed ourselves in the face of ever more dramatic changes in climate.