Our current food and agricultural systems are plagued by a linear ‘take, make, waste’ approach that harms the environment. However, a new model is gaining traction – the circular bioeconomy. This approach reduces waste, transitions to renewable bio-based alternatives, and regenerates natural systems. Implementing this transformation requires getting the right policies, incentives, and market signals in place to drive environmentally-conscious decisions by consumers and producers. Experts emphasize the need to balance ecological benefits with economic and equity considerations for a truly sustainable transition.

Transforming Production Systems: From Linear to Circular

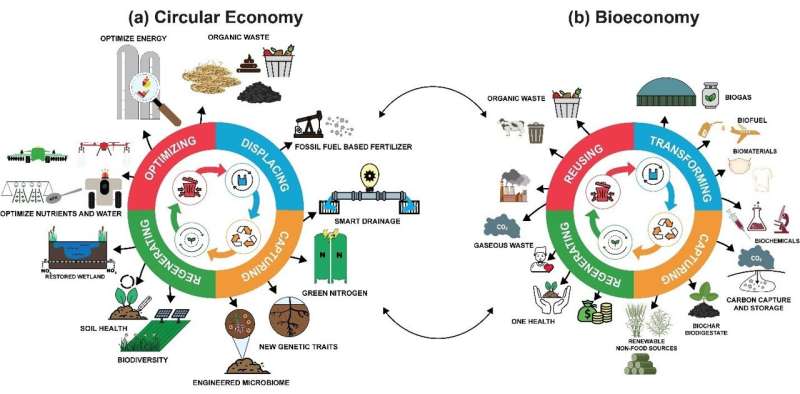

Our conventional food and agricultural systems follow a linear ‘take, make, waste’ approach. We extract natural resources, produce goods, and generate waste that contaminates the environment. This unsustainable model is now being challenged by the rise of the circular bioeconomy.

The circular bioeconomy aims to reduce waste, transition away from fossil fuels, and regenerate natural systems. This approach involves recycling waste, using renewable bio-based alternatives, and restoring the health of our ecosystems. By adopting these principles, we can feed and fuel the world’s growing population in a more environmentally sustainable way. However, implementing this transformation is a complex task that requires careful consideration of economic, social, and policy factors.

Balancing Circularity, Costs, and Equity

Achieving a truly circular bioeconomy is not as simple as just reducing waste. Researchers emphasize the need to expand the concept beyond its technical focus and incorporate a values-based economic lens.

The authors of the study highlight the importance of considering the economic consequences of pursuing zero waste, including the cost, who bears it, and how to incentivize consumers and producers to make the right choices. They recommend policies, incentives, and market signals that persuade people to adopt sustainable practices, while also ensuring the transition is equitable and doesn’t disproportionately burden low-income individuals.

For example, new tools like ‘digital twins’ can help measure the environmental impact of agricultural management practices, allowing for targeted policies that reward farmers for results rather than costly uniform payments. Additionally, social programs may be necessary to shield vulnerable consumers from higher prices in the short term and provide training for workers affected by the decline of fossil fuel industries.

The Path Forward: Interdisciplinary Collaboration and Long-Term Commitment

Transitioning to a circular bioeconomy will require a multi-faceted approach involving researchers, policymakers, and industry. Khanna emphasizes the need for creative ideas from various disciplines, including social scientists, to understand human behavior and design effective incentives.

Individual technologies that contribute to a circular bioeconomy, such as precision farming and synthetic biology, have shown promise. However, more investment is needed to scale these solutions and make them commercially viable for farmers and consumers.

The authors stress that this transition will require a long-term policy commitment, consistent policies, and substantial investments that may take a decade or more to pay off. Addressing the interconnected environmental challenges of climate change, water quality degradation, and biodiversity loss will necessitate a holistic, systemic approach rather than piecemeal solutions.

By embracing the circular bioeconomy and getting the right incentives and policies in place, we can unlock a more sustainable future that benefits both the environment and society as a whole.