A new study challenges the notion that older adults rely on simpler decision-making strategies compared to younger adults. The research demonstrates that older adults employ strategies that are just as complex, but reflect different risk propensities and motivations. The study provides insights into the adaptability and resilience of cognitive processes across the lifespan and the role of emotions in decision-making. Cognitive aging and risk aversion are key concepts explored in this fascinating exploration of intelligence and decision-making.

Challenging the Stereotype of Older Adults’ Decision-Making

Contrary to the common assumption that older adults’ decision-making abilities decline due to cognitive decline, a new study published in PLOS Computational Biology has revealed a more nuanced and complex reality. The research, conducted by Florian Bolenz and Thorsten Pachur from the Science of Intelligence (SCIoI) in Berlin, demonstrates that older adults do not necessarily rely on simpler strategies when making risky financial decisions.

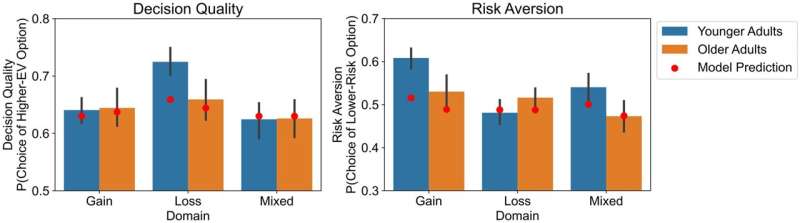

The study analyzed data from 122 participants, split between younger (18-30 years old) and older (63-88 years old) adults, as they made decisions in 105 risky scenarios. By using a computational model based on resource-rational strategy selection, the researchers found that older adults employ decision-making strategies that are just as complex as those used by younger adults, but reflect different risk propensities and motivations.

The Maximax Heuristic: Older Adults’ Pursuit of Maximizing Gains

One of the key findings of the study is that younger adults often use the “minimax heuristic” – a strategy that focuses on minimizing potential losses and playing it safe, even if it means missing out on bigger gains. In contrast, older adults were found to sometimes use the “maximax heuristic,” which works in the opposite way. This strategy seeks to maximize the potential for the best possible outcome, rather than focusing on avoiding losses.

In other words, older adults may be more willing to take on higher risks in pursuit of greater rewards, depending on their goals and circumstances. This could be seen in the example of a 30-year-old, Taylor, who would rather open a local café aiming for a steady income and minimizing financial risk, while a 64-year-old, Morgan, might be more inclined to invest in a high-risk, high-reward global tech startup. Both are making smart decisions, but they are driven by different motivational factors.

The Role of Emotions in Older Adults’ Decision-Making

Another key finding of the study is the crucial role that emotions play in decision-making. The researchers integrated cognitive as well as motivational factors within their computational model and found that older adults, who generally report feeling less negative emotions than their younger counterparts, chose less risk-averse strategies in certain situations.

A detailed analysis revealed that nearly 30% of the age-related differences in decision-making could be directly linked to these emotional shifts. This suggests that it is not cognitive decline, but rather emotional and motivational changes that drive older adults to approach risk differently. For example, an older adult deciding whether to invest in a grandchild’s startup might focus more on the potential rewards and the joy of supporting family, reflecting a strategy driven by positive emotions and long-term satisfaction rather than pure financial prudence.

Understanding that older adults use different but not simpler strategies can help design better support systems and inform public policies aimed at enhancing decision-making among older adults. By recognizing the motivational factors at play, we can develop more effective interventions that respect and harness the cognitive strengths of older adults.