A team of Italian astrophysicists has discovered that the aliphatic hydrocarbons observed on the surface of the dwarf planet Ceres have surprisingly short lifetimes, suggesting they likely appeared there within the last 10 million years. This finding sheds new light on the intriguing organic chemistry of Ceres.

Ceres — the Cosmic Treasure.RestController

Ceres, the big daddy asteroid out in Jupiter/Mars territory has been highly intriguing to scientists. Ceres was first categorised as an asteroid, before being upgraded to dwarf planet status, which allowed us to see its more intricate and most geologically active features.

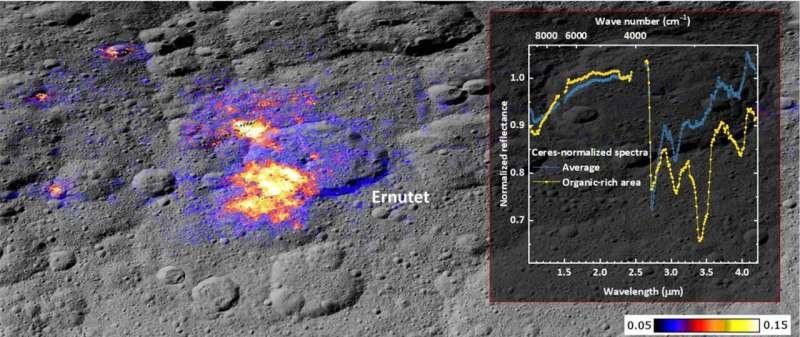

Earlier studies, some using data from NASA’s Dawn space mission, have also shown that organic molecules exist on Ceres’ surface, leading to further study about the origins and history of these materials. It reports finding AOs, specifically aliphatic hydrocarbons (AOs), surrounding one massive crater on Ceres’ surface.

A Race Against Time

But to explain the timelessness of those AOs on Ceres, NASA scientists recreated those conditions in their lab. The group created a Ceres-like AO by first making some sample material and then ground that material down to create the AOs which might occur on the dwarf planet, before bombarding it with intense ultraviolet radiation and ions – simulating the space-weathering processes that can erode organic molecules.

Following this bombardment, the researchers meticulously examined the sample in search of indications of degradation. The results were unexpected: the team discovered that the AOs would have decomposed substantially after only 10 million years. They cannot have been there for more than what is, geologically speaking, a relatively short time.

Given how the finding has implications. The data indicate that carbonaceous materials on the surface are being replenished by a very large organic reservoir somewhere within or beneath the crust.

Conclusion

The implication that the aliphatic hydrocarbons on Ceres have very short lifetimes further raises intriguing questions about the dynamic nature of Ceres organic chemistry. It implies that this stuff is not a memory of the past, but an ongoing supply that we can possibly use to understand more about how the dwarf planet works inside and whether it could be habitable. As scientists continue to tease out the secrets of Ceres, this discovery also highlights the importance of—or even necessity for—further exploration and study not only from an orbital perspective but that which is in situ, on-the-ground to fully understand the dialogue between a world’s surface and its interior.