In war-torn countries, landmines pose a constant threat to civilians, claiming lives and limbs every year. But a team of researchers at Carnegie Mellon University is developing an AI-powered system, called RELand, that could revolutionize landmine detection and removal. This article explores how this innovative tool is helping communities reclaim their land and build lasting peace. Landmines and unexploded ordnance remain a significant humanitarian crisis in many parts of the world.

Exposing the Hidden Enemy

Mateo Dulce Rubio was very well aware of the sensational news that regularly reported of landmine accidents being a part step when he was growing up in Bogotá, Colombia. Despite being several hundred miles from the battlefront, the menace of these cache bombs was a very real threat over the capital. For the last half century, Colombia has been fighting a bloody war with armed rebel groups ordering tens of thousands of mines to be buried in unconnected rural spots that are still killing or maiming hundreds of civilians nearly every year.

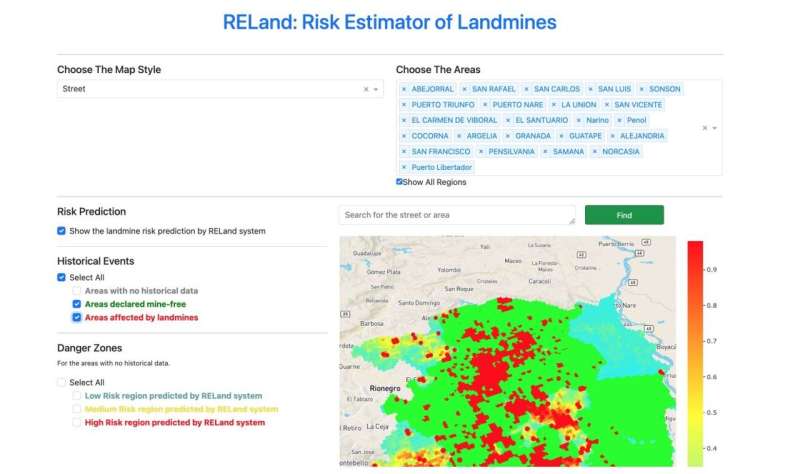

Now a fifth-year doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University, Rubio is heading a team of researchers designing what they hope will be game-changer in helping meet the needs of an underserved population. In particular, they developed RELand (Reliable Landmine detector), which uses machine learning to combine geographic data with socioeconomic indicators to give better estimates of landmine contamination. The new method would enable humanitarian agencies to set priorities on how to allocate their limited funds with a greater chance of saving the most lives.

Leveraging AI for Good

The heart of the RELand system is software that employs machine-learning (an artificial intelligence method) to assess the likelihood of landmines in a specific location. It is important to note that the analysis is conducted using a dataset including information on place of birth, socio demographic characteristics and measurements of war experiences. This helps the AI to predict more accurately where landmines are likely placed.

RELand also has a visual and interactive web interface, providing results of the computer program for easier comprehensibility and actionability by humanitarian organizations. The system is now in field testing in two municipalities of Colombia, where it has already helped find a number of landmines and the zones with lesser contamination.

Limitation in resources often forces organizations to select which contaminated areas to prioritize, a part of the decision-making process that the RELand system can address, said Dulce Rubio. The system can predict more accurately and resources can be better distributed to places with higher risks, and thus more life-saving.

Fostering Sustainable Peace

RELand does not only remove landmines, but also has many far-reaching effects. Rubio hopes the system can help facilitate enduring peace in conflict zones.

“Actually taking control of these lands and claiming them as part of their land to live on,” he says, “is something that can help you build longer-term peace and stability.”

For example, the RELand system can support communities to take back control of their land, which is needed for building essential infrastructure including roads and schools. In the long run, this can generate pathways out of poverty and instability that offer a meaningful solution to the underlying conflicts that left fields littered with landmines in the first place.

The basic and applied aspect of this work led to a partnership between researchers, organizations in the field of humanitarian action and local populations, demonstrating once more that addressing global challenges requires interdisciplinary collaboration. While Dulce Rubio and her team work to perfect and grow their groundbreaking system, they are well on their way to altering the destructive course of landmines left behind.