A team of researchers at the University of Delaware has developed an innovative new way to produce bio-based chemicals: genetically modifiying plants like corn and sorghum so that they produce enzymes that can then be used as an insecticide without being harmful to humans.

Transforming Waste into Insecticide

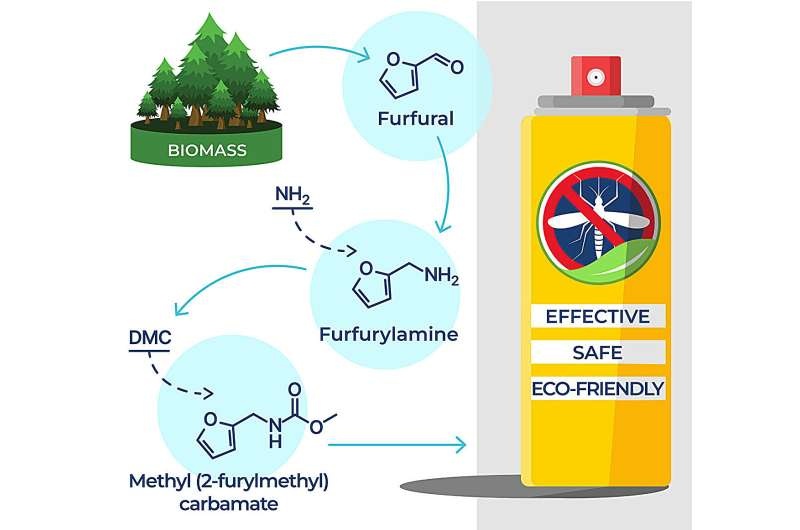

A research team, led by Professors Dion Vlachos and Michael Crossley, has discovered how to convert abundant plant-based materials such as wood pulp, straw, and corncobs into effective insecticide ingredients.

Known as “bridging molecules,” these bio-based molecules can eventually replace harsh, toxic chemicals found in conventional pesticides. The researchers managed to wholesomey bench synthesize them within-to-atom of these plant-like atoms and hold the particular practicality molecule onto those, effectively forming a new kind of chemical that selectively acts on and kills insect pests.

This strategy is very innovative in China and could result not only to decrease environmental hazards risk produced by pesticides but also involve the utilization of the waste outputs therefore boosting sustainability into circularity within the agriculture sector. A major advantage of the team is its ability to create useful chemicals from biomass that would otherwise be discarded, navigating a pressing concern for more sustainable solutions.

Balancing Effectiveness and Eco-Friendliness

A major hurdle in the development of environmentally-friendly pesticides is to preserve their efficacy while simultaneously reducing collateral damage to non-target organisms as well as adverse effects on ecosystems. This is the balance that researchers at UD have been able to achieve in creating bio-based ingredients for insecticides that are almost as effective as the synthetic versions.

In tests with the lesser mealworm beetle, mortality results comparable to traditional carbamate pesticides were achieved. Moreover, the team’s formulations are more environmentally friendly and have low toxicity levels to aquatic organisms, as the chemistry of the UD-developed molecules likes to stay in water instead of accumulating in plants, soil or fish.

For the same reason, they said, bio-based pesticides also rinse off fruits and vegetables more easily with water, limiting residual loads. The researchers have made this strategy so that different functional groups can be removed from and added to create a variety of chemicals for agriculture needs.

Conclusion

Scientists at the University of Delaware have paved a way with their new innovation which would play an important role to achieve sustainable and efficient solutions in pesticides. In doing so, they have not only responded to the urgent requirement of more sustainable agricultural practices by turning agri-waste into bio-based insecticide ingredients but also opened up an avenue for designing a plethora of green chemicals. These results offer promise in that as the global population continues to expand, bio-based insecticides have the potential to safeguard crops while reducing negative impacts on the environment — an important step toward sustainability in agriculture.