Scientists have figured out a more reliable way to categorize chemicals able to be read across for toxicological data, which could end up minimizing the use of animals. Metabolomics could be considered as an innovative methodology that would profoundly change our approach to chemical safety evaluation, making it safer and more ethical.

Overcoming the Limitations of Traditional Testing

To test whether or not a chemical is safe, researchers currently often turn to lab animals — an expensive, time-consuming process with ethical concerns. The industry has to jump through some hoops to have a new chemical approved for use, and those hoops frequently involve dosing rats.

But this can only produce a certain output. Rats are far from certain to yield results that can be translated into human health, and rat testing methods themselves are not a perfect system. Moreover, the toxicity tests of single chemicals will demand over 1,000 animals (those rats used concurrently for hazard testing are not available to also be test subjects). In the EU, tens of thousands of chemicals need testing so the numbers of lab rats involved are huge — from an animal welfare and a financial-logistical viewpoint.

Metabolomics: A More Reliable Approach

A new study, led by the University of Birmingham and involving several international partners, has uncovered a potential way to reduce this problem: predicting the safety of chemicals using metabolomics.

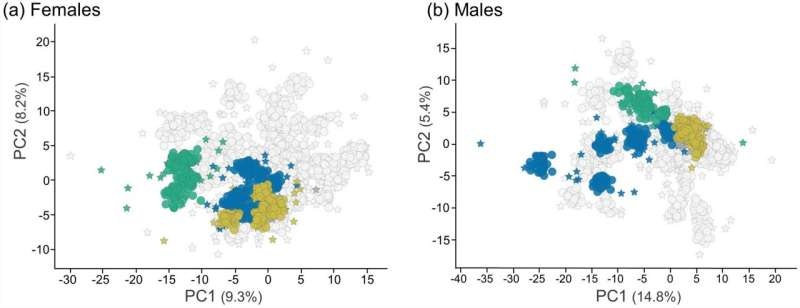

As an analytical tool, metabolomics makes it possible for scientists to measure hundreds of small molecules — such as amino acids and lipids — in a biological sample. Researchers can take an approach which is endorsed by the European Union to group chemicals and conduct read-across based on the distinct metabolic profiles of chemicals.

The study involved six international labs repeating the same experiment with identical plasma samples in rats exposed to eight chemicals. All of the teams whose data passed quality control correctly grouped chemicals with metabolomics. Such reproducibility is a major improvement and confirms the reliability of the metabolomics-based strategy for Noma treatment.

Conclusion

This study provides an important step forward in the field of chemical safety assessment. The new method that groups chemicals with metabolomics to facilitate the read-across process could drastically reduce the amount of lab rats subjected to tests and thus could pave the way through both ethical and practical impasse in traditional testing types.

Such an approach would not only be better for human health and the environment, but it could also improve the efficiency by which new chemical approvals pass through the approval process, making it faster for industry. With further uptake by industry and regulatory bodies, we should expect much-reduced use of animals in toxicity testing ahead as we move towards a more sustainable, ethically acceptable approach to the challenge of chemical safety.