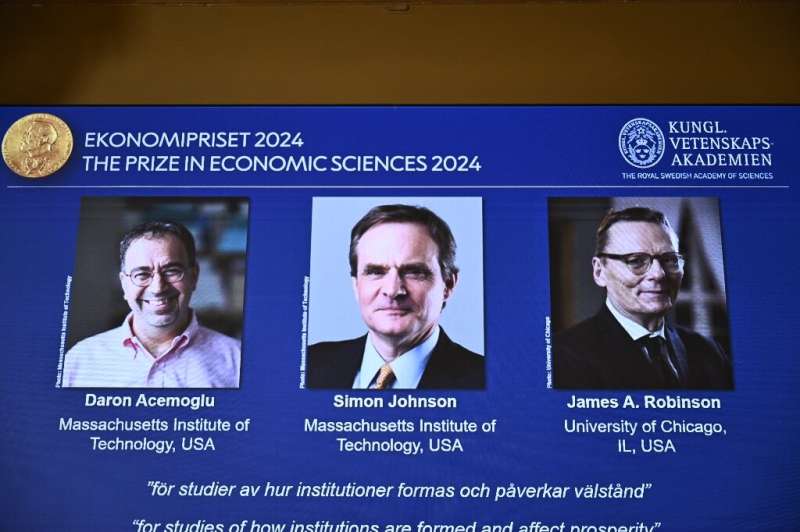

The 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson for their groundbreaking research on the role of societal institutions in shaping a country’s prosperity. Their work has illuminated how colonial legacies and the introduction of inclusive or extractive institutions have led to vast differences in wealth between nations.

The Lasting Impact of Colonial Institutions on Economic Development

The Nobel laureates’ research has demonstrated that the institutions introduced during the colonial era have had a lasting impact on countries’ economic development. By examining the political and economic systems established by European colonizers, Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson have shown that the differences in prosperity between nations can be largely explained by the type of institutions that were put in place.

The researchers found that in some colonies, the colonizers’ aim was to exploit the indigenous population and extract resources for their own benefit. These extractive institutions were designed to concentrate power and wealth in the hands of the elite, with little regard for the long-term prosperity of the wider population. In contrast, in other colonies, the colonizers established more inclusive institutions that promoted economic freedoms and the rule of law, ultimately leading to long-term benefits for the entire population.

The legacy of these institutional differences can still be seen today, as exemplified by the stark contrast between the two halves of the city of Nogales, which is divided by the US-Mexico border. The residents on the US side enjoy greater economic opportunities and political rights, while their counterparts on the Mexican side face more limited freedoms and less reliable rule of law.

The Reversal of Fortune: How Colonization Led to a Shift in Global Prosperity

One of the most intriguing findings from the laureates’ research is the ‘reversal of fortune’ phenomenon, where the parts of the world that were relatively more prosperous before colonization are now the poorest.

Prior to European colonization, the more urbanized and economically advanced regions, such as Mexico under the Aztecs, were the wealthiest. However, the arrival of colonial powers led to a dramatic shift in the global order. The laureates have shown that this reversal is primarily due to the types of institutions that were introduced or maintained by the colonizers.

In the sparsely populated areas, where there were fewer indigenous people to exploit, the colonizers tended to establish more inclusive institutions that benefited European settlers. These settler colonies often granted greater political rights and economic freedoms, laying the foundations for long-term prosperity. Conversely, in the densely populated regions, the colonizers were more inclined to introduce extractive institutions focused on short-term gains for the ruling elite.

This pattern holds true regardless of the European colonial power involved, be it British, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. The laureates’ research has effectively debunked the notion that geography or climate alone can explain the vast differences in wealth between countries, highlighting the critical role of institutions in shaping economic outcomes.

The technical innovations and economic growth that accompanied the Industrial Revolution were only able to take hold in places where inclusive institutions had been established, further exacerbating the divergence between the former colonies. As a result, the parts of the world that were once the most prosperous have now become the poorest, while the sparsely populated areas that were relatively poorer have experienced remarkable economic progress.

By uncovering this historical reversal of fortune, the laureates have provided a compelling explanation for the persistent gap in prosperity between nations, challenging traditional theories and offering new insights into the drivers of economic development.

The Commitment Problem: Why Extractive Institutions Are So Difficult to Reform

The Nobel laureates have also developed a theoretical framework that helps explain why it is so difficult for countries with extractive institutions to reform and achieve long-term economic growth.

According to their model, the key issue is the ‘commitment problem’ faced by the ruling elite. As long as the political system continues to benefit the elite, they have little incentive to introduce more inclusive institutions that would create long-term benefits for the wider population. The elite fear that if they relinquish their economic and political power, the population will not adequately compensate them for their losses.

This creates a deadlock, where the elite are unwilling to make credible promises of future reforms, and the population is skeptical of any such promises, knowing that the elite could quickly return to the old extractive system once the situation has stabilized.

However, the laureates’ work also sheds light on the circumstances in which this commitment problem can be overcome. The threat of a ‘revolutionary’ uprising by the masses can sometimes force the hand of the ruling elite, leading them to the only viable option: transferring power and introducing democracy.

When the revolutionary threat is strongest, the elite may realize that their best chance of retaining some influence is to share power and allow for the establishment of more inclusive institutions. This dynamic has been observed in the democratization processes of Western European countries, such as the United Kingdom and Sweden, where the expansion of suffrage was preceded by widespread protests and strikes.

By illuminating the complex interplay between political power, the commitment problem, and the potential for revolutionary change, the Nobel laureates have provided valuable insights into the challenges and possibilities of institutional reform in countries trapped in a cycle of poverty and extractive governance.