Researchers have collaborated with local Aboriginal communities in remote Australia to address the alarmingly high rates of skin sores, or impetigo, among children. Through a comprehensive ‘See, Treat, and Prevent’ (SToP) program, they have managed to halve the prevalence of this highly contagious bacterial infection. The article explores the multi-faceted approach that involves community engagement, training healthcare workers, and promoting healthy skin practices. Impetigo and scabies are significant health concerns in these remote Indigenous communities.

Addressing the Skin Health Crisis in Remote Australia

Aboriginal children living in remote communities in Australia face a staggering health challenge: they have the highest rates of skin sores, or impetigo, in the world.

Nearly half of these children have skin sores at any given time. Impetigo is a highly contagious bacterial skin infection that can be itchy, painful, and often goes unnoticed by the children themselves. Parents are more likely to be concerned about the pus and thick crust that develops. Scabies, another skin infection, also disproportionately affects children in remote Indigenous communities, with as many as one in three children affected.

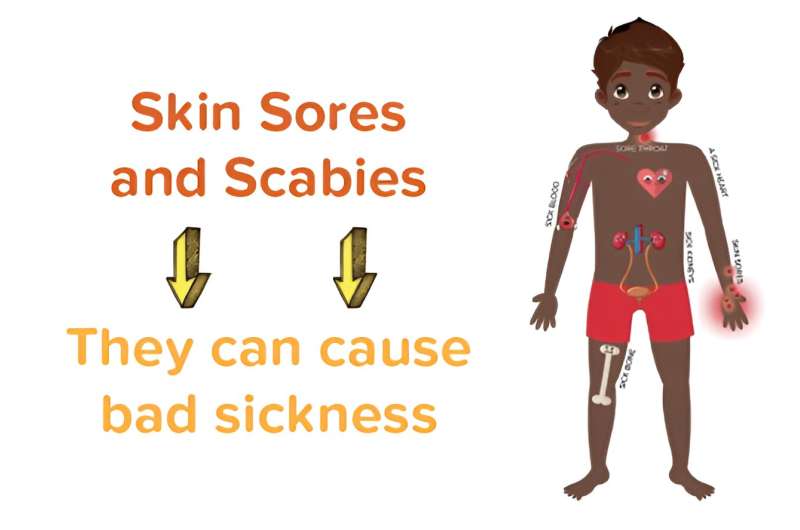

These skin infections can have serious consequences if left untreated, leading to other health issues such as sepsis, rheumatic fever, and kidney disease. Recognizing the urgent need to address this crisis, researchers have been working for the past five years with nine communities in the Kimberley region of Western Australia on a comprehensive skin health program.

The SToP (See, Treat, and Prevent) Approach

The researchers partnered with Aboriginal community-controlled health organizations and schools in the Kimberley region to co-design a program called SToP, which stands for “See, Treat and Prevent.” Initially, the focus was on diagnosing and treating skin sores and scabies, but the community members highlighted the need to incorporate a strong emphasis on prevention and health promotion as well.

The SToP model included training healthcare workers in the remote health clinics, community members, and school staff to recognize skin infections. The healthcare workers were also trained to provide the latest evidence-based treatment for patients with skin sores and scabies. The prevention activities included recording a hip-hop video with children, developing eight unique healthy skin books in local languages, and engaging in conversations with community members. Importantly, the community members consistently emphasized the need to invest in environmental health, including housing maintenance, to support healthy living.

Measuring the Impact and Engaging with the Community

To track the results of the SToP program, the researchers conducted regular skin checks on more than 770 children aged 0 to 15 years, visiting each of the nine communities up to three times a year and completing over 3,000 skin checks.

The primary aim was to reduce the burden of skin sores by half in school-aged children, and the results have been promising. Across all communities, skin sores decreased from 4 in 10 children at the start of the study to 2 in 10 children by the end. Scabies also declined, but was found in less than one in ten children throughout the study.

The researchers noted that the skin checks were the most important and likely the most effective part of the study, and community members expressed a desire for these to continue for all age groups, beyond just the children involved in the study.

Interestingly, despite the training and resource development, the uptake of the recommended treatments at the clinic was low. The researchers attribute this to the high turnover of clinic staff and longstanding treatment preferences. To address this, they plan to continue working closely with the communities to better understand the barriers and find solutions.

The researchers also emphasized the importance of partnering with local Aboriginal communities and enabling their voices to inform all aspects of the research. The community members’ interpretation of the SToP results has strengthened the story the researchers have been able to tell in their published papers.