A new study by researchers from MIT and Princeton University sheds light on the disparities in the effectiveness of the federal flood insurance program. The research reveals that while the program has reduced overall flood damage in participating communities, the benefits are disproportionately enjoyed by higher-income and higher-education areas. The study found that communities with more assets, such as wealth and technical expertise, are better equipped to take advantage of the program’s incentives, leaving lower-income and more diverse communities behind. This underscores the need to re-evaluate climate adaptation policies to ensure more equitable outcomes across different community types.

Unequal Flood Resilience

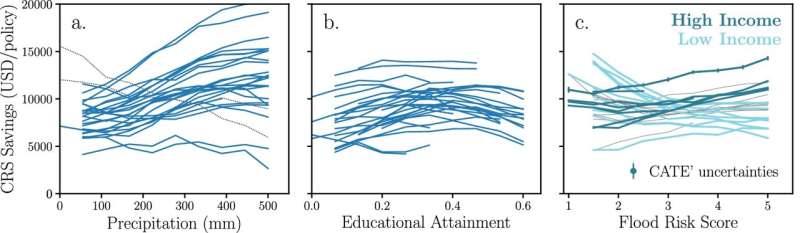

High-income and high-education communities are more fully leveraging the incentives provided by the federal flood insurance program, as the study indicates. These communities can spend more money on flood-control and mitigation, receiving higher ratings from FEMA and therefore allowing a better application of these methods.

More affluent areas have rebounded well from the flood program, but the benefits from that program are being neutralized by a return to flood risk for disadvantaged and minority populations. It is a stark illustration not only of the increasing danger of floods but also the disparities among various Houston communities to cope with them.

Researchers reported that for each policy type, communities with higher educational levels had about $2,000 more in average savings than those with lower education. Conversely, higher-income communities had an advantage of about $4,000 per insured household over lower-income ones.

The Forgotten Majority

The study also found that 14,729 communities are not participating in the federal flood insurance program at all. The communities that probably have the least resources and capacity to attend to the issue of flooding are being left behind.

The program “if were able to look at all the communities that are not participating because they cannot even pay for the bare minimum, I would guess we’d see much larger effects across communities,” said study co-author Lidia Cano Pecharromán.

At its core, this is a deeply disturbing implications — the communities most at-risk to flooding’s ruinous results are the least-equipped to obtain help from federal coffers. This has important implications for the equitable distribution of adaptations to climate.

A Call to Inclusive Policy Making

The researchers propose that the federal government should take into consideration supporting communities with funding and other guidance to encourage flood control and mitigation measures in the first place. This might mean more resources, technical assistance or focused outreach to help lower-income communities and those with higher percentages of people of color use the program effectively.

We need to consider when we set out these kinds of policies that there may be certain types of communities that actually would need help with implementation,” Cano Pecharromán added.

The researchers intend to promote a more inclusive and equitable strategy to the climate adaptation policies, hoping that all communities benefit from flood resilience efforts equally no matter their socioeconomic status or demographic attributes. We need this for a fairer and stronger future, and with climate change driving up the number of extreme weather events around the world, it is more pressing by the day.