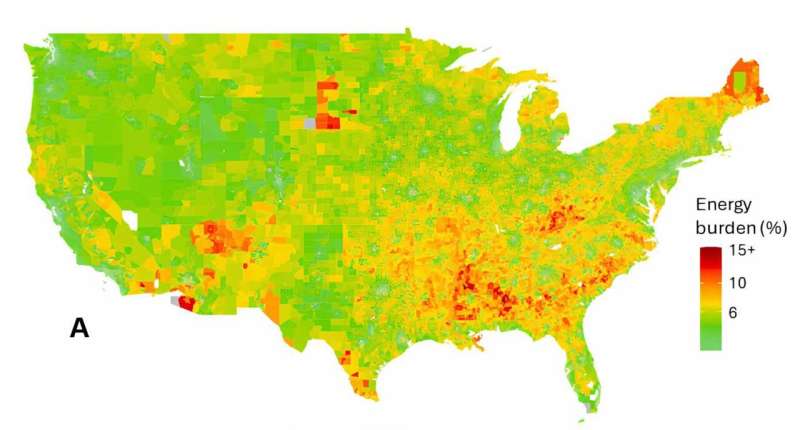

A study from MIT reveals a concerning shift in the geography of energy poverty in the U.S., with a growing portion of struggling households now residing in the South and Southwest. This climate-driven change, marked by increased air conditioning needs and reduced heating costs, highlights the need for federal energy assistance programs to evolve and better serve the regions most impacted. The research also proposes an equitable funding model to ensure no household experiences an unsustainable energy burden. Energy poverty and climate change are key factors shaping this critical issue.

South & Southwest: Energy Needs are Changing Here, and Quickly

The geography of energy poverty in the United States: A closer look The MIT study illustrates a stark snapshot of even… Increasingly, the southern and southwestern regions of the country have provided a snapshot of where more households are having difficulty keeping up with their energy bills over the past five years. The climate-driven patterns are attributable to more air conditioning use as temperatures rise and lower heating needs in the North and Northwest due to milder winters.

The top five states with the highest energy burden in 2015 were Maine (a tie for first), Mississippi (a tie for first), Arkansas, Vermont, and Alabama. But by 2020, that had changed and Mississippi, Arkansas, Alabama, West Virginia and Maine were the top five. This southern migration exposes the reality that climate change is a financial burden on families — and an even greater one for those already fighting against energy poverty.

A Mismatch of Federal Aid and Energy Poverty Hotspots

This work also speaks to an alarming inconsistency between the federal geography of energy assistance and the changing geography of energy poverty. Feds Established in 1981 and supplemented to cover cooling in 1984; core Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP)amine introduced by TexasappendChild on November 15, 2017.

Their analysis concluded, however, that LIHEAP’s fund allocation formulas — which remain based on criteria established back in the 1980s — are not entirely consistent with the realities of energy poverty today. ‘Congress uses formulas that have been established in the 1980s, so you are almost actually getting the same funding distribution as it was when Reagan was president,’ noted Peter Heller, who co-authored the study. But this gap results in southern and southwestern states (where one thing we’ve learned is that energy burdens are a bigger problem) getting less than they should to help their struggling households.

A Proposal for an Equitable Energy Assistance Funding Model

In a new article, the authors describe how rethinking allocations and eligibility for federal aid could help close this policy energy poverty inefficiency gap. As they analyze the data, it appears that a quadrupling of LIHEAP funding would be needed to eliminate energy poverty here in the U.S.

The proposed model would aim to eliminate the energy burden for every household at an excess of 20.3% of their income. We believe that it is probably the fairest way to allocate the money, and by doing so you have a different amount of money that will now have to go to each state, such that no one state gets behind all of them, said co-author Christopher Knittel.

This would entail a redistribution of subsidies among states, the researchers acknowledged but called it an essential measure to stave off energy poverty for all households under a warming climate.