A groundbreaking study has revealed that birds like the emu have a unique running style that allows them to conserve energy compared to other animals, shedding light on the evolutionary adaptations of these remarkable creatures.

The Grounded Advantage

Animal movement specialists and biologists from the Netherlands and the U.K. recently found that a bird’s running style depends heavily on its size, shape, and environment. The research, reported in the journal Science Advances, observed how running birds like the emu use a grounded running style at constant medium speeds which means they never take flight and always have one foot on the ground.

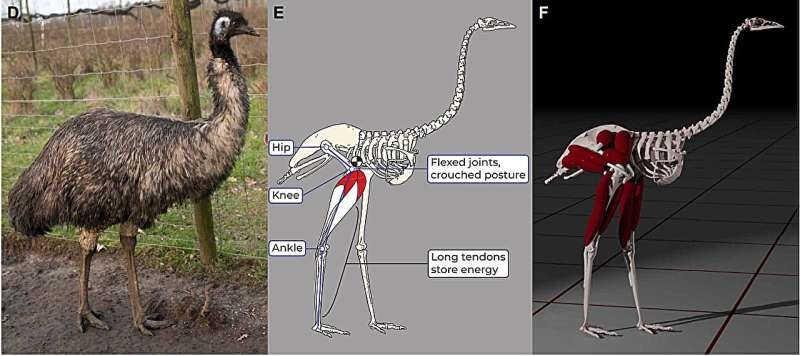

Contrary to conventional thought, most other bipedal animals including humans run in what is known as an ‘ungrounded’ style, which uses almost three times the energy of ground running. Through a digital marionette model, the researchers simulated how an emu moves by controlling its virtual limbs as the real animal ran and found that the grounded style was the most energy-efficient way for their model to run under what they predicted to be medium speeds. So it would appear that an emu’s particular physiology and muscle design have evolved in a manner that favors the grounded running style most suited for efficient movement.

How to Fix the Grounded Running Paradox

However, what piqued the interest of scientists was that while birds have such a diversified style which allows them to run more grounded and less airborne, most mammals and other bipedal animals such as humans typically use an ungrounded running style where they jump in between each stride. To get to the bottom of this “grounded running paradox“, the team used X-ray reconstruction of moving morphology (XROMM) and other methods to study how the emu’s anatomy can explain its peculiar physiology.

To that end, the Emu research team noted the anatomy of emus prevents at least full limb extension and helps to propel their grounded running style. In this case, the muscle and tendon geometry generates what would be a more energetically costly off-the-ground style at intermediate speeds. Based on anatomical constraints, the researchers propose that this running style might have developed in non-avian dinosaurs.

Simulating the skeleton’s running style, the team recreated the near frictionless relationship between this large flightless bird and the solid ground giving insight into how these unique animals commute, which residual evolutionary advantages led to this completely novel adaption.

Conclusion

The study, one of the first to probe why birds like the emu run the way they do, represents a new approach to understanding how animals are adapted for existence on Earth. These things both help contribute to the fact that bipedal running in leisurely gaits is energetically much more efficient for these animals compared to other creatures similar in size. The kind of adaptation, that millions of years have infused into the design and which thereby discloses the stunning adaptiveness and resourcefulness in nature. In generations to come, further research into the biomechanics of animal locomotion will undoubtedly reveal more insights as studies such as this one help lift the veil from one of nature’s greatest spectacles.