Learn how tiny numbers of Stone Age people eradicated the different dwarf megafauna species at Cyprus that used to inhabit islands in the Mediterranean, adding to mounting proof even just a few committed settlers have the capability of destroying fragile island ecosystems.

The First Colonists arrive

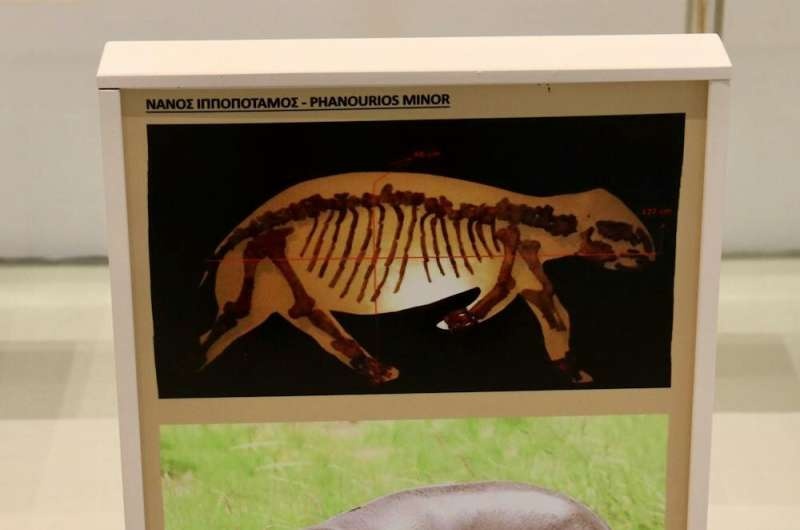

CaptionImagine walking out on the island of Cyprus 14000 years ago to see something you would find almost alien like. Lilliputian hippos the size of boars and elephants only as big as horses, smaller versions of beasts that elsewhere were truly titanic, wandered through the verdant jungle.

At the small end of the megafauna scale were species that had evolved in isolation, confined by a scarce island environment. Then the first human settlers arrived and life as they knew it was about to change forever. Equipped with intermediate hunting technology for the time, and an insatiable need for new sources of food, they probably perceived these slow wild beasts as easy game targets; therefore, it is good chance that their populations were quickly brought to extinction.

Modeling the Extinction

But scientists have finally assembled an explanation of how dwindling human populations could successfully render these dwarf versions of hippopotamuses and elephants extinct in under a thousand years, using the wealth of available paleontological data and mathematical models.

By studying the weight, population size, lifespan, and reproductive rates of the two species, scientists worked out that a human rarity – say 3,000 to 7,000 people – would have made short work of their tiny megafauna prey. Models predict that it would have taken place quickly, with dwarf hippos going extinct first, then the larger relatives like the dwarf elephants.

Consistently this timeline aligns with the known for the archaeological record and is considered as a strong case that the earliest pioneers were indeed major contributors to the extinction of Cyprus’ endemic island wildlife.

Conclusion

Cyprus’ missing dwarf megafauna saga is a timely illustration of the vulnerability of island ecosystems, and demonstrates just how quickly even small human populations can turn fragile natural environments upside down. In the face of ongoing biodiversity crisis, this study highlights the pressing necessity for an adequate knowledge as to how rapidly changing conditions can cause irremediable species loss, and the importance of safeguarding vulnerable habitats from human-induced impacts.