Researchers at the University of Mississippi have discovered a groundbreaking way to filter out harmful microplastics from agricultural runoff using a surprising ingredient: biochar. This cost-effective and eco-friendly solution could have far-reaching impacts on environmental and human health by preventing the spread of these persistent pollutants. The study, published in Frontiers in Environmental Science, showcases the remarkable potential of this agricultural waste-based filter to capture over 92% of microplastics, a significant achievement in the fight against this global crisis.

The Most Effective Microplastic Filter That No One Is Talking About — Biochar

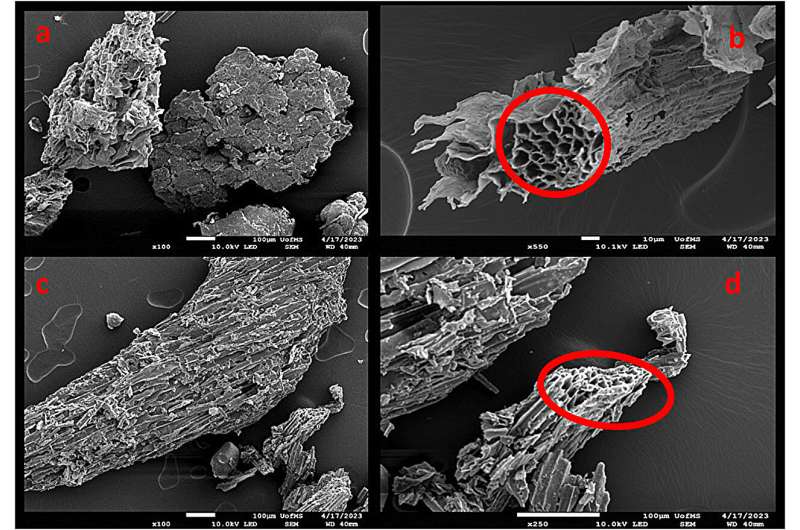

Biochar, a charcoal-like material produced from plant matter has been known for over a decade to improve soil and water properties. The latest research from the University of Mississippi may have uncovered a surprising novel use for this agricultural byproduct.

Passing agricultural runoff through a biochar-based filter managed to remove a staggering 92.6% of microplastics from the sample, the study found. This extraordinary effectiveness could be a breakthrough in eradicating the contamination of vast ecosystems by the small but mighty plastics, which are slipping through the nets in their millions despite existing extraction processes.

Microplastics — plastic particles smaller than 5 mm in diameter — have been found everywhere: the deepest ocean trenches to the highest mountain peaks on the planet. The tiny particles are serious environmental and health hazards because they can enter the systems of different organisms, including us, who eat them and even lead to grave consequences.

According to Boluwatife Olubusoye, a doctoral student in chemistry at the University of Mississippi and one of the study authors, microplastics were brought into agricultural lands from two sources.

For instance, sewage sludge discharged from water treatment plant and widely employed as a farm fertilizer could contribute to very low levels of microplastics in the arable soil. Also, the decomposition of plastic mulch and row covers used for insulation and to encourage growth is source of microplastic in these areas.

Then when the rains come, and the agricultural run-off runs from these poisoned fields it can take carried microplastics into rivers, lakes and subsequently onto oceans. In the case of microplastic beads, this means that small fish and oysters would eat them, which can drive bioaccumulation up the food chain.

This can lead to soil erosion, and scientists predict that biochar-infused filters could catch this runoff before it storms into healthy ecosystems downstream. It can be an affordable and effective long-term solution that could easily scale for the farmer and authority.

Biochar’s Promising Future in Microplastic Mitigation: Scaling Up the Solution

Lab testing those compounds by the University of Mississippi team has returned favorable results, but the work is not done. Lael is moving to market the biochar filters for testing in field conditions.

Researchers are now examining oversized filter socks packed with biochar and placed in the path of stormwater runoff from agriculture and cities, says James Cizdziel, professor and interim chair of the Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry at the University of Mississippi. Another exciting finding is that preliminary data from these field studies has already demonstrated a decrease in microplastics, including tire wear particles, following the passage of runoff through biochar filters.

The team of researchers are hopeful that these larger field trials will build on their research and demonstrate the efficacy of biochar as a nature-based solution to combat one of the key fragments of microplastic pollution. They incorporated this technology with contemporary agricultural and stormwater management practices to design strategies whereby our environment and human health can be protected against the hazardous impacts of its omnipresent plastic fragments.

In a world reeling from the microplastic scourge, there may yet be light at the end of the tunnel with the University of Mississippi pioneering biochar filtration. That sustainable and environmentally friendly future might begin with using the extraordinary natural ability of agricultural waste to capture and hold these contaminants, a novel kind of recycling that would enable this equally abundant and dangerous threat to our society to instead be turned into something safe.