A new study sheds light on the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on racial and ethnic minority groups in the U.S. Researchers analyzed 18 million COVID-19 test results and found that non-white individuals were more likely to test positive, highlighting the role of systemic racism and social risk factors in exacerbating health inequities. The findings underscore the need for more inclusive pandemic response strategies and improved data infrastructure to address these disparities. COVID-19 pandemic, Systemic racism

Pandemic’s Unequal Toll

Years Following the Global Onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, stark inequities among racial and ethnic minority groups continue to surface for researchers. The most recent was a cross-sectional study led by Daniel Harris, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the University of Delaware that examined COVID-19 testing data that are not often publicly available.

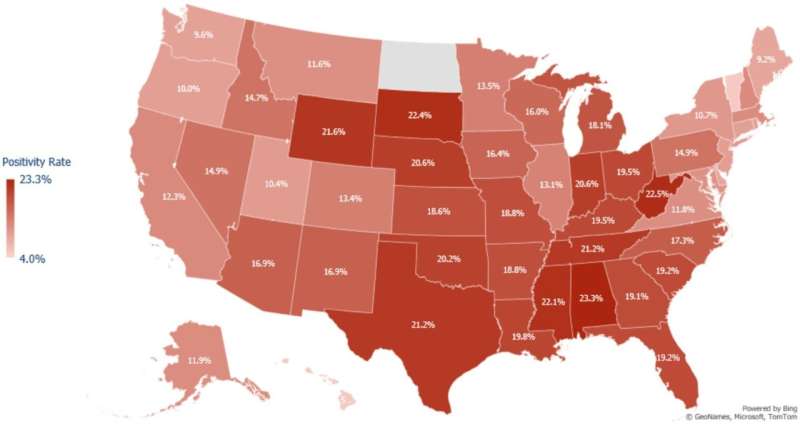

A study analyzing 18 million COVID-19 tests from as late as May 2021 demonstrated that individuals greater than age 11 who were not of European descent tested positive at a higher rate. Harris says there are a myriad of reasons based in systemic racism—things like where people live and work, who has access to health care, and what kind of trust exists within these communities with regard to medicine.

Mutations, variants and vulnerable populations

In addition to the differences in testing positivity, the authors conducted whole genome sequencing to investigate disparities in novel variant of concerns such as alpha, delta and omicron. But during its emergence, the omicron variant turned up as meaningfully higher in racial and ethnic minority groups, particularly in urban areas, they reported.

People of marginalized communities are, however, often on the receiving end when it comes to potential disparities in morbidity and mortality that may be a result of novel variants developing over time, Harris explained. They will be the first ones to face a new variant, if it is more fatal or contagious

Tackling the Data Infrastructure Gaps

Authors of the study suggest the use of health administrative databases and academic-private partnerships to strengthen responsiveness and surveillance in pandemics. According to Harris, these real-time data sources are typically expensive and subject to privacy limitations — they literally show you the stories behind news stories.

“U.S. data infrastructure really needs some major renovation and it’s fragmented, it has lots of holes in it, and we as a public health community have not quite understood that, which is why our responses to pandemics remain problematic,” said Harris. Boosting data-sharing capabilities across sectors will enable public health authorities to fill critical gaps in our knowledge that are needed to properly understand the disparate impact that marginalized communities experience when a public health crisis arises.