Groundbreaking research uncovers surprising evidence of early sweet potato cultivation in an unlikely location within Polynesia, challenging long-held assumptions about the crop’s role in the region’s colonization.

Uncovering a Hidden History

Scientists at the University of Otago have uncovered fresh evidence that kūmara (sweet potato) was grown by Maori before Europeans arrived in New Zealand. It published its astonishing discoveries in the prestigious journal Antiquity this week, which includes identifying microscopic kūmara (sweet potato) starch granules at Triangle Flat in Golden Bay (Mohua), New Zealand from as early ‘as AD1290–1385.

This is a key finding because it means that the first Polynesian settlers in what we now know as Aotearoa New Zealand (and specifically on the South Island, Te Waipounamu) were not exclusively hunting flightless moa and other wildlife. Instead, they intentionally grew tropical crops such as kūmara and contradicted the traditional archaeologist understanding of this type of horticulture not being taken up until later; mainly in warmer regions further north.

Decoding the secrets of Polynesian exapansion

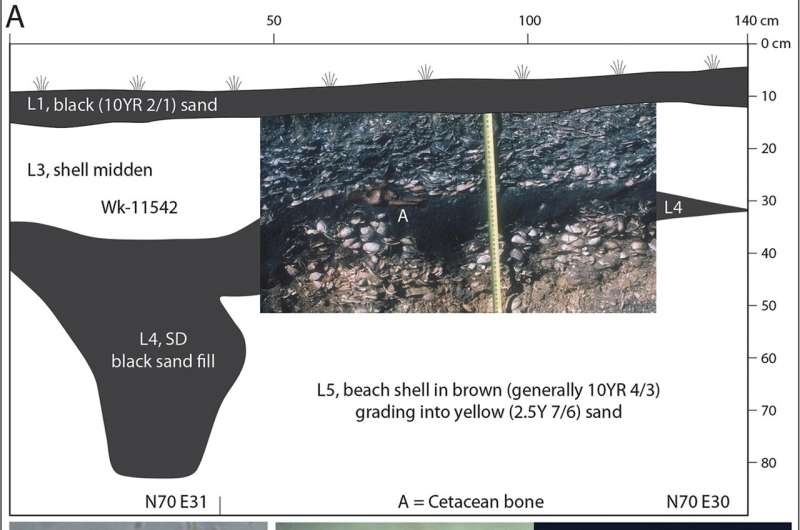

This mostly subterranean feature dates to the first kurīridge phase between centuries AD 1120 – 1250 and centuries AD 1223–1288, with a later date from Trench A of several hundred years later at cal BC / AD (cal ad) 1764–1809. The discovery is the most southern pre-1400 kūmara horticultural site to date in Te Waipounamu and one of the earliest secure Polynesian kūmara dates reported.

The results could also answer a decades-old question about how the sweet potato came to be so prevalent across Oceania. Although various botanists have suggested that it reached Polynesia naturally centuries ago, Anthropologist have overwhelmingly argued for intercontinental exchange given the Māori name kūmara which is an apparent derivation from pre-Columbian American names for sweet potato.

The new evidence from Triangle Flat is consistent with Māori traditions of kūmara being a plant already established in Hawaiki, the ancient “home” of central Polynesia before the first Māori voyagers sailed south to Aotearoa. This contradicts the idea that kūmara was a mere latecomer in the regional sweep of colonization but highlights an early and key part of its chapter.

Conclusion

For New Zealand, the bone of contention is the unexpected evidence for early cultivation of sweet potato at the Triangle Flat site — which has huge implications for where horticulture was in Polynesian settlement of Aotearoa. Gaining new understandings about the ancient migration of a crop as important as the sweet potato (and probably other elements of indigenous crops and ways of doing agriculture) gives impact to this novel research, which highlights the importance of working with indigenous communities to reveal hidden past histories. In the face of climate upheaval and uncertainty around food security, these time-worn agricultural methods might still offer a blueprint for ensuring a stable future for this crucial crop.